My Lifelong Silent Retreat

By Emily Simon

For the first 21 years of my life, I never said or did anything at all.

It’s a way of living that the average recluse would sympathize with. I truly lived some of my most formative years inside my head. I think it comes naturally to most artists and writers. A large part of our work is to observe, re-interpret, and then create. I can feel it still, as I jot down these words. Old habits of silence and suppression tug at my sleeve, attempting to invalidate my firsthand experience of being a writer. Shying away from action became a subconscious self-inflicted punishment, propelling me to a state of halfway living, restricting myself to my mind and thoughts.

Tucked away in an unsuspecting cubby of the nightstand in my bedroom is a stack of 10 or so journals, all of which have been consistently kept up with since I was eleven years-old. I took each one out of hibernation, hunting for uncomfortable answers to uncomfortable questions. It was a lovely afternoon flipping through pages filled with scribbles reanimating the worst versions of myself in attempts to piece together where, why, and when this started. I have narrowed it down to a few standout memories where nothing in particular happened, but were elaborated in detail for up to 20 pages. 20 pages of absolutely nothing, but evidently everything.

I am four or five years old, at the top of an aluminum slide on a playground—the ones that absorb heat and burn your legs as you squeak down. At the bottom, my mother beckons for me to slide down. She’s standing next to a man named Greg who used to visit sometimes. I never recall him leaving. He’s standing next to my mother, hands tucked away in denim pockets. I can’t see his hands and I never do. Greg has this smell I could recognize to this day. It was a cologne with a musk I liked—very strong. I knew it meant Greg.

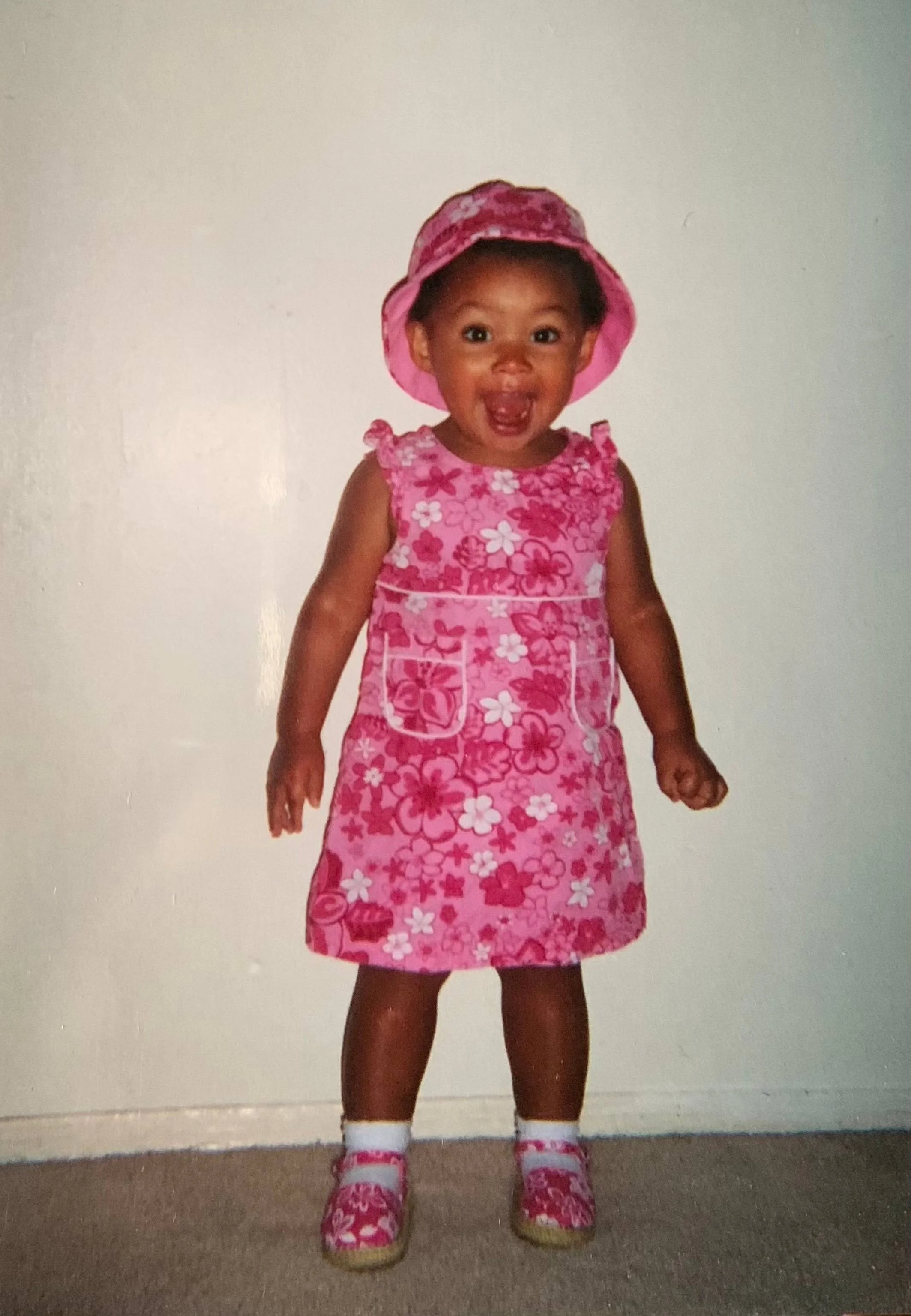

Around the same age, we are moving houses across the highway to the “dry-side” of town further away from the bay. Standing atop a plastic bin, I feel its waxy surface slipping underneath my toes. I wore an indigo ruffled bikini with pink, green, and purple polka dots. My mother takes a photo while I hold my arms in front of my stomach, because even at five years old, I was aware of the fat around my belly and knew it wasn’t supposed to be there. Vanity is a construct you don’t quite fully grasp when you’re a little girl, but there exists an understanding that it is to become the bane of your existence.

On the playground of the elementary school I moved to there’s a maple tree with roots crawling out from under the dirt, revealing themselves like it’s a secret between me and the tree. At a middle school basketball game, my classmates pass around an edited photo of me saying I look like the girl from the polar express movie, the one with the braids. They call me “polar express girl" for the rest of middle school and high school.

The journals go on: the pink goop from strawberries and granulated sugar at my grandma’s house, skipping out on her funeral because her face looked unfamiliar in the casket. Liverwurst and salami on white bread, wood paneling of a downstairs living room, the stinks of sulfur from Florida well-water, blue American Spirits, natural wine, Greg’s musk that reminds me of mourning. Every now and then I catch a whiff of its memory. So what is it? Grandma, Mom, Greg, the boyfriend, the friend? No, it’s me. It’s an incarnation of a self I let linger, then slowly rot in the dirt for 21-years. So I remained in a constant state of mourning..

Idealism states that reality is a fundamentally mental experience. Materialism says that it’s the corporal that motivates our conscious experience. If you were to ask me a year ago, I would berate you with a slew of excuses as to why idealism was the superior of the two creeds. It felt safer to look at my life in-between the lines, as if I were writing the screenplay to a movie seated in the back row, scribbling away. The characters are out of my control, unsuspecting, and nothing has consequences when it's a narrative depicted on a screen far out of reach. All of those memories jotted down on paper were evidence of a half-conscious but fully real experience. Scribbling in a state of mania on and on for 20, even 30 pages about everything, about nothing, meant I was far removed from the real danger. Whatever that was.

I observed, I did nothing, I listened, I did nothing, I had no opinion. My quarter-life crisis was drastically over-due. I was a walking ball of anxiety ready to blow. It had reached a point where I could physically feel pain in my chest, every-living waking hour of the day. Bottles were thrown, relationships were severed, and police were called. I got up the morning after, the dust had not yet settled. My roommate, in the living room, sat looking uneasy. My partner wouldn't pick up the phone. It’s what happens when someone who is continually silent suddenly decides to speak. As I reached the tipping point the damn rapture. It scared a lot of people away, naturally.

I ran out of paper in my diary. I meant to get a new one a while ago. I also ran out of mental capacity for the lifestyle of letting things slip between my fingers on purpose so they’d have no impact. I burned the candle on both ends and then some, so that flames licked the skin off my fingers; only bone was left to bear the consequences of emotionally withdrawing myself to a single stream of consciousness that never knew when to shut the hell up. Something I had realized in my afternoon of soul searching through lonely journal pages, was that I myself was lonely. I was a lonely little girl, despite all these graphic depictions of people in my pages. I was too shy to put myself in there with them.

Giving myself the permission to not be lonely felt like stripping in a room full of people who bathed me as a baby—as odd and comedic as it may sound. I was hot and red in the face to let people be adjacent to this new, naked me. They’re laughing, saying, “we’ve known you this whole time.” Thinking of it like this makes real life seem like one big joke, followed by a gratified sigh. If you show up, others will show up for you too.

Was I a “writer,” too hyper fixated on delving into narratives as a form of denial for life? Am I even a writer? Maybe you have asked yourself these same questions. No experience is ever unique. When the lights turned on for the first time ever, it was like stepping into a new skin, tight and ready to be worn in. I can tell you that in this new body, the cerebral is quieter, quiet is good. Real life, the palpable, is loud. Loud is better.